Into The Deep

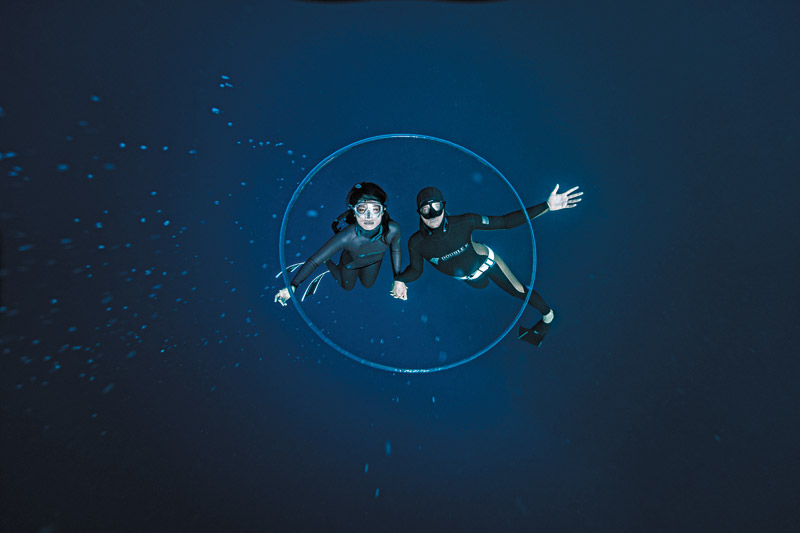

America’s free-diving champions — Daniel Koval and Kristin Kuba — have found their life’s calling well below the surface of the ocean.

For national free-diving champions, life partners and South Kona residents Daniel Koval, 31, and Kristin Kuba, 26, diving to depths of 100 meters is more than a passionate and competitive endeavor — it’s a highly spiritual pursuit.

“Free diving is not about just diving as deep as you can. It’s really more like diving into yourself and letting go of any fears, doubts or worries,” says Koval.

“When you make a deep dive, time stops and nothing really exists except for that single moment. It’s an opportunity to escape reality and be in another world for a few minutes at a time,” Kuba adds.

The couple is in the water six days a week to train for this physically and mentally demanding sport. They are also diving safety partners. Koval says they “attend church” by diving at Hōnaunau Bay every Sunday morning.

Free-diving is a way of life for Daniel Koval and Kristin Kuba, who share a passion for the sport.

MIKE HONG PHOTOS

Koval broke the U.S. free-diving record in July at the Vertical Blue competition held at Dean’s Blue Hole in the Bahamas. He reached a depth of 102 meters (335 feet), setting the new national record and becoming the deepest self-propelled free-diver in the nation.

Kuba, for her part, also set two records this year — at the U.S. Bi-fin national (71 meters, or 233 feet), as well as her depth of 70 meters (230 feet) in constant weight at the CMAS World Championships in Turkey back in October. In addition, Koval and Kuba were the first Americans to represent Team USA in the U.S. Free-diving Federation, competing against 150 divers from more than 30 countries.

And together, they are now the deepest free-diving couple in American history.

Both Koval and Kuba got their start in the sport through their love of spearfishing.

Originally from Orange, California, Koval started spearfishing at age 12 along The Golden State’s coast, becoming intrigued with the fantastical underwater world he witnessed.

“I became a scuba diver and eventually moved to O‘ahu at age 19 to start working in the dive industry,” he recalls. “I got a job at the Pacific Beach Hotel aquarium, which had a 25-foot tank, where I had to care for the stingrays and eagle rays. I would free-dive the tank, which would later help me to feel more comfortable in free-diving competitions.”

Daniel Koval and Kristin Kuba perch themselves atop an underwater shelf.

PHOTOS COURTESY DANIEL KOVAL AND KRISTIN KUBA

Eventually, Koval took a free-diving course at Free-diving Instructors International (where he currently teaches) and through the mentorship of owner Martin Stepanek, started progressing and began training intensely in 2014. He started out free-diving at the Sea Tiger, a famous wreck off O‘ahu, located at a depth of 40 meters (132 feet).

Training at a competitive level, however, did not always go well.

“I was plagued with equalization issues, and I was not flexible enough to handle the intense pressures at depth,” Koval recalls. “I was scared to reach depths deeper than 60 meters (200 feet).”

After two years of struggling, he finally let go of his fear and developed the flexibility for much deeper depths through consistent training. Within a few months, his work had paid off and he entered his first international competition in 2016.

“Martin helped me continue to progress, taught me things I didn’t know and made me realize what I was capable of,” Koval says.

“Yes, it is scary to dive to 100 meters, as I really don’t know what’s waiting for me down there. But you have to let go of all fears, worries, and tension in order to descend to these depths. You have give yourself to the sea.”

Kristin Kuba

Astoundingly, Kuba didn’t even know how to swim until about six years ago. Born and raised on O‘ahu, she worked in the beauty industry and says she hadn’t really been an ocean person. But she began spear-fishing with friends, which led to her interest in free-diving, and she began taking courses. Entering her first international competition in 2017, Kuba had a great showing, making every single dive.

“Free-diving really helped me figure out who I was,” she says. “In order to dive deeper, you have to be honest with yourself and face what’s really holding you back from going any deeper.”

Free-diving requires the diver to change his or her physiology to descend to great depths. It requires holding one’s breath for nearly three minutes.

You have to be flexible to accommodate the 11 atmospheres of pressure (162 pounds of pressure per square inch) that occurs at 100 meters,” Koval explains. “Your lungs will compress to the size of golf balls, so you must learn to equalize pressure (like popping your ears on an airplane) and repeat that process the entire way down during the dive.”

Free-divers have to train to resist and tolerate the urge to breathe, and not panic. This is because they are not actually low on oxygen. Rather, they are high on carbon dioxide.

According to Koval, when you are really low on oxygen, you don’t get that sense of panic, that urge to breathe. Instead, it is a euphoric feeling, a tingling, accompanied by visual disturbances and the sense that you could go on forever.

“Many people give up, get scared and quit,” says Koval of those first learning breath control.

But when they conquer those fears, the rewards are great.

“Past 30 meters, when your lungs get compressed, you become so negatively buoyant you no longer need to kick anymore,” he adds. “This is my favorite part of the dive, as you can go from 30 to 100-plus meters without moving a single muscle as gravity pulls you down. It feels as if you were flying to the bottom of the sea.”

Yes, free-diving can be dangerous, but that’s usually because, as Koval explains, people get careless and safety measures are not followed.

“Safety is easy in free-diving,” he says. “Free-divers should always work with a partner who are trained to handle any hypoxic issues.”

Koval says that 99 percent of free-diving fatalities occur at very shallow depths — around 5 meters — if there is no one to meet the diver and escort them to the surface. This is called shallow water blackout. (During competitions, for example, there’s always a physician on the platform and pure oxygen that divers can intake to recover after the dive.)

Koval and Kuba hope to be ambassadors of the sport and are aiming for an Olympic berth in 2028. They’ve helped enhance spectator enjoyment from shore by introducing underwater drones to follow the action.

“We believe we can promote the sport by reaching deeper depths and breaking more records,” says Kuba.

Whether training, competing or simply enjoying the experience, Koval and Kuba love how non-threatening and natural free-diving is. There are no scuba bubbles to scare fish. It’s transcendent and relaxing, a quiet, silent world of beauty.

“When I was at Dean’s Blue Hole in the Bahamas for my 102-meter national record, I remember beyond 70 meters, it is pitch black,” says Koval. “I actually need a light that is zip-tied to the hood of my wetsuit so I can just see the line a foot away from me. As the light shines on the little particles of the deep, you get this feeling as if you’re just a little speck in outer space. It’s a very humbling experience.”