‘Camp Saved My Life’

B.K. Cannon always finds a way to leave her mark on others, including camper Addie and counselor Napua.

BY CAROL CHANG

An annual camp on the North Shore of O‘ahu that offers a week of free fun for kids ages 7-18 is about to move indoors this year due to the coronavirus. But the requirement for this virtual camp will be the same: All campers must have cancer or have been through it before.

Founded upon love and loss in 1985 by parents and medical professionals, Camp Ānuenue (meaning “rainbow”) is run by a wacky group of cancer survivors and friends who just want to give kids a break.

President and co-director B.K. Cannon is a perfect example of what seven days of fun can do to help heal sick kids who feel isolated and discouraged by the disease.

To meet her today, you’d never suspect her near-tragic start on this planet.

Taking one last group photo at the conclusion of 2019’s “Camp Anuenue Goes to Space.” PHOTOS COURTESY CAMP ANUENUE

Barbara-Kimberly Cannon is a healthy cheerleader for life who lifts up everyone around her — including her own parents — and she has an especially soft spot for the shy ones. Plus, she’s worked 10 years in her other career as an on-screen actress; coaches at a respected LA acting school and just returned from filming a Netflix production in New York.

“Camp saved my life in ways medicine could not,” she declares.

In a way, she never left, returning year after year until today and taking on more leadership roles as she grew.

“My first blessing was beating the cancer, but my second was finding this camp,” she says. “Having had cancer gave me the passion to make sure Camp Ānuenue continues.”

Cannon finds her groove in her role as Kris in the Golden Globe-nominated series The Politician, which airs on Netflix. PHOTO COURTESY NETFLIX.

The gregarious child was only 3 and 1/2 when doctors diagnosed her with stage 4 neuroblastoma. The long list of tough medical weapons used to fight it over the years — surgeries, radiation, relapses, body casts, transfusions, chemotherapy and more — is only exceeded by her long list of TV and film roles later on.

“I’ve had just as many surgeries and procedures in remission as I did in active treatment,” she says. “But that’s the gig. Cancer is a lifelong journey.”

Like Cannon, many former campers are now doing well in life, and smiling a lot more. Children don’t like to stand out or feel different, explains Carol Kotsubo, a retired pediatric oncology nurse who helped found the camp with Dr. Robert Wilkinson of Kapi‘olani hospital and others.

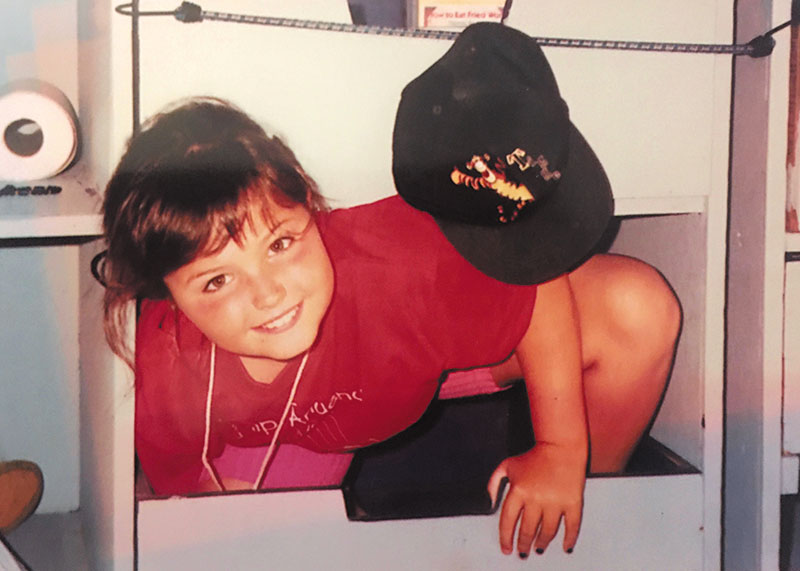

Playing around during her first Camp Anuenue in 1998

“They want to do what children do. They want to run, to play, to sing and to have friends,” she says.

Under the camp’s safe conditions with medical help present, they can. Getting them to laugh and smile can change everything at the hospital, too.

“A new self-confidence allows the child to continue treatment with a determination to get it over with and to resume normal life,” says Kotsubo, noting that 80 percent of children do survive cancer.

Here are some examples:

• Arielle Underwood was born with an aggressive tumor on her tiny foot caused by fibroma sarcoma. Doctors amputated that foot to save her life, yet she eventually learned to dance ballet, ride a bike and now has a thriving commercial art career while teaching English in Japan. Her mother assembled a photo album to help her young classmates understand why she had that strange prosthesis at the bottom of her leg, and later wrote and illustrated the self-published book Arielle’s Footprints: A Child’s Journey to Surviving Prematurity, Cancer and Amputation.

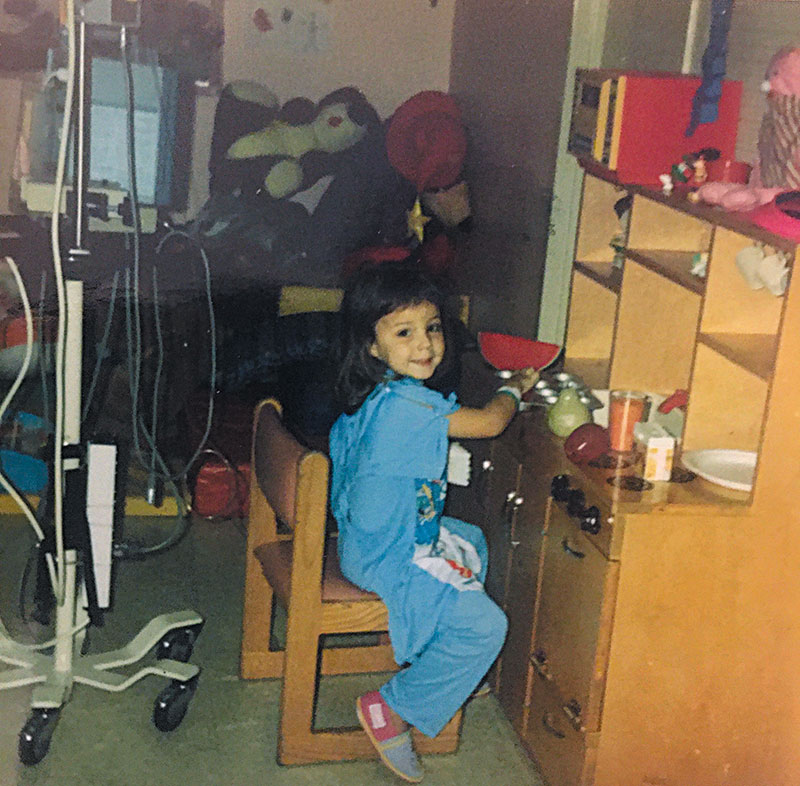

Getting ready for surgery after she was diagnosed with cancer at age 3. PHOTOS COURTESY CAMP ĀNUENUE

“Camp Ānuenue was a wonderful, freeing adventure for her,” recalls mom AnnMarie Manzulli. “It was a big awakening for her about how lucky she was for what didn’t happen.”

• Grace, 13, skipped a chemo treatment for the muscle tissue cancer rhabdomyosarcoma to attend her first camp and, after meeting the other kids, came away with renewed strength and a smile on her face.

“It made me want to keep fighting,” she declares in video testimony on the camp website. “I realized all these people were alive, and I could do it too.”

• Just like Cannon, Hawai‘i Island camper Ruth Mersburgh, 18, also acquired neuroblastoma early. But after one year as a human pincushion, fighting nausea and isolation, she says, “I kicked cancer’s butt! And something those commercials with bald kids don’t show you is the mental/emotional/social toll that these treatments take on kids and how they reach recovery. That’s what Camp Ānuenue is for.”

• Even the few who don’t make it through have bestowed their legacy of compassion, empathy and fighting spirit upon their parents. Kāne‘ohe’s Irving and Cathi Chun, both social workers, helped establish and run the camp. Their daughter McKell died of leukemia before it even opened.

Irving calls their two decades with Camp Ānuenue “a phenomenal blessing for us personally and everyone there … When not in that circle, you don’t understand this cancer bond,” he adds. “There’s more joy than people realize.”

• Award-winning videographer Ken Libby and wife Joyce joined the Ānuenue ‘ohana in 1990. Their son, Scott, enjoyed two camps and one day of a third one before he succumbed to rhabdomyosarcoma at age 9.

“He liked it better than anything other than Christmas,” recalls Libby, who came back for 22 camps in order to film and carefully edit the children’s experiences at no charge as a keepsake for them and their families. “I felt I had to shoot it, but most of the time I was crying. It was therapy for me, almost supernatural.”

• Tom and Trudi Cannon also have been enriched. Now living in Phoenix, they’ve enjoyed forever friendships with other camp parents, doctors, nurses and understanding bosses. Their upbeat child gave them the strength to help fight her cancer. “B.K. has buoyed us until now,” Trudy says.

They watched her graduate from Le Jardin Academy and Mid-Pacific Institute, complete a year of home-schooling while auditioning in LA and earn a liberal arts degree there from Mount St. Mary’s University.

While at Mid-Pac for her junior and senior years, Cannon naturally joined its performing arts program and worked with teacher R. Kevin Doyle. He got to watch her blossom as a “big personality” and leader.

“She was already B.K. — I can’t claim the credit,” he laughs. “Everyone loved her right from the start and gravitated toward her. She was just a delight, and a consummate professional.”

Cannon was a familiar face in the TV series Switched at Birth, The Politician, Sorry for Your Loss and Sin City Saints; she was in both the TV movie and series Flight 29 Down, and clinched guest roles in hit shows like Bones, Grey’s Anatomy, Chicago Fire, Glee, The Mindy Project, ER, Criminal Minds, Law & Order: LA and House.

“I’ve been lucky enough to support myself doing it,” she says, “and I enjoy the process on the set.” The rejections in between are a challenge, she admits, but fighting cancer prepared her for it. “I don’t know who I’d be if I didn’t have cancer, and I would do it over again.”

She became close friends with her cabin counselor Alison James. They even share a pet dog between their homes in California. So when American Cancer Society withdrew funding in 2014 from cancer camps nationwide in favor of more research for a cure, the pair turned the camp into a nonprofit with volunteer counselors and staff, supported by vigorous fund-raising campaigns. (Cost is $70,000 per camp, plus $1,500 per camper.) They also pay to fly in campers from Guam, Saipan, American Samoa and the Marshall Islands.

“B.K. is full of energy, the opposite of me,” says James, a shy research biologist-turned pharmaceutical rep who volunteers as camp vice president and co-director. “It’s the scientist and the actor; I’m the producer and she’s the director. I mentored her through surgeries and body braces, and then the tables flipped really fast when I was diagnosed myself with breast cancer in 2014.

“Amazingly, B.K. went with me to every appointment, surgery, etc. She rescheduled her auditions in LA and made it very positive — we laughed at every appointment,” James recalls. “The nurse even thought I was crying and sent for a social worker!”

One camp video shows Cannon and fellow actress Britt Robertson in a remarkable live-streaming effort that brought $55,000 into the 2017 budget. More recently, Cannon coached Robertson for her latest film role, in which she portrays singer-songwriter Jeremy Camp’s first wife, who died of ovarian cancer shortly after their wedding.

“When she accepted the part, we talked about it,” Cannon says. “She wanted to do an authentic portrayal.” I Still Believe stars KJ Apa and Robertson and came out in March.

Researchers have visited and studied the camp over the years, including Marc Rich, who observed: “I do not recollect ever meeting a victim at Camp Ānuenue. Instead, I remember a camper in a wheelchair playing basketball with his friends. I see a young boy’s smiling face covered with ice cream. I recall an adolescent girl dancing the hula …”

To donate, visit campanuenue.com, and email campanuenue@gmail.com to learn more about upcoming virtual camps.