Sampling The Skies

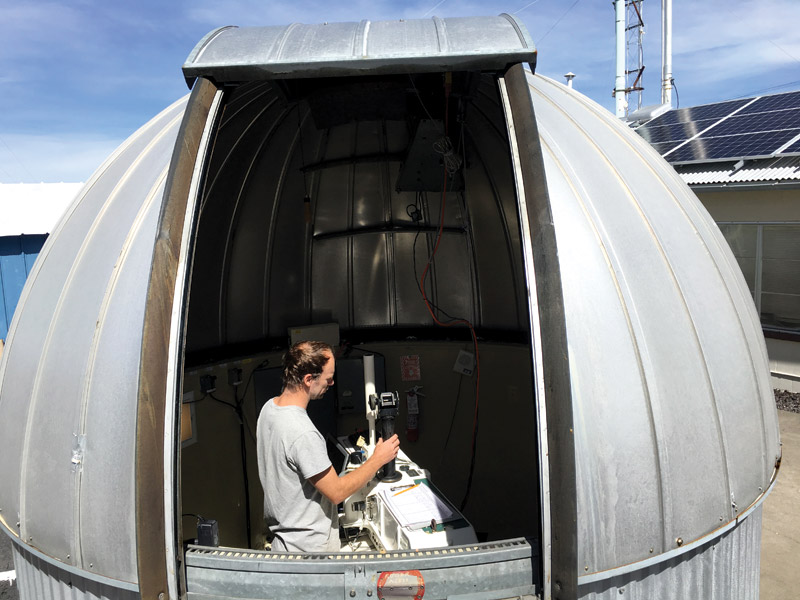

Matthew Martinsen takes a column ozone measurement in the Dobson Dome.

Some of the planet’s most important work takes place at 11,141 feet on the northern flank of the Big Island’s massive Mauna Loa volcano. At Mauna Loa Observatory, part of NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory’s Global Monitoring Division, scientists measure rising carbon dioxide concentrations, ozone, solar radiation, and both tropospheric and stratospheric aerosols.

What all this means is that station scientists collect, track and report the data that will give researchers a minute-by-minute report card about earth’s atmospheric health.

“We basically monitor five main areas that can cause a warming or cooling of the atmosphere,” says station chief Darryl Kuniyuki.

As a “baseline” monitoring station, Mauna Loa Observatory is one of four NOAA stations around the world that are situated in prime, pristine environments far from vehicular and other pollutants.

“We have clean, well-mixed air samples from air that has traveled 2,000 miles in any direction,” says Aidan Colton, an environmental geoscientist. “All of our data is public and can be downloaded by research universities, governmental entities, and by our ESRL headquarters for Global Monitoring in Boulder, Colorado.”

Sister stations are located in Barrow, Alaska, the South Pole and American Samoa.

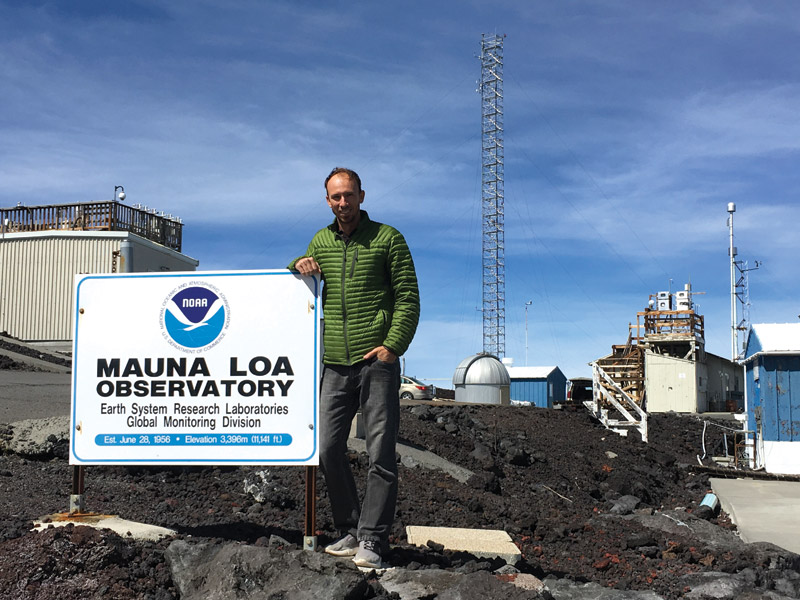

Aidan Colton verifies operations for solar instrumentation.

Originally built in the 1950s, the station (basically a “shack” in the beginning) was under the auspices of the United States Weather Bureau, as it was called until 1970. Its mission at the time was to simply measure air temperature and pressure with a few solar measurements as well.

In 1957, they began to continuously measure solar radiation and total column ozone, and in 1958, carbon dioxide. That’s made it the longest continually running station for collecting and tracking atmospheric data on the planet.

Supporting the observatory, other data collection locations operate at Kulani Mauka Site, a rain collection area, Cape Kumukahi Site, a flask sample site, and at National Weather Service Hilo Airport site, where “ozonesonde” balloons are launched once a week to measure stratospheric ozone values and water vapor instruments are launched once per month to provide a profile of water vapor at different altitudes.

Administrative offices for the station in Hilo and Boulder, Colorado, analyze and process the data.

Colton explains that the solar radiation monitoring systems look at harmful UV wavelengths, the kind that can cause skin cancer, while aerosol measurements search for particulates in the atmosphere that can affect our climate.

Aidan Colton stands in front of the Mauna Loa Observatory entrance sign.

“These include dust, sea salt, car exhaust, dirty coal-burning particulates, and any other particles that are small enough to float up and bind with water vapor to form clouds,” he says.

In all, the station hosts 70 different projects measuring more than 250 different elements in our atmosphere.

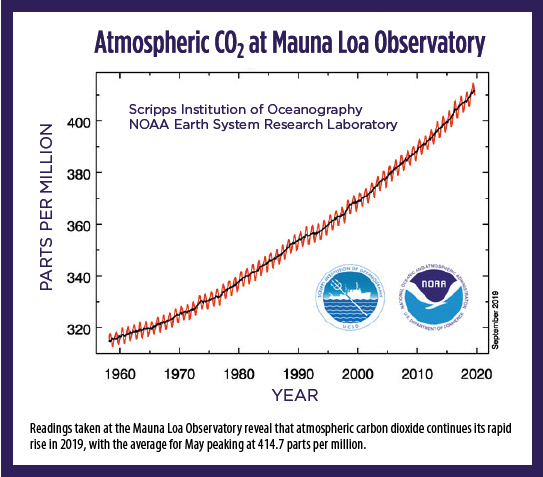

According to a recent statement issued by scientists from NOAA and Scripps Institution of Oceanography at University of California San Diego, by the end of 2018, Mauna Loa Observatory recorded the fourth-highest annual growth in the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide in 60 years of record keeping, with four of the five largest increases recorded in the last seven years.

They also reported that atmospheric carbon dioxide continued its rapid rise in 2019, with the average for May peaking at 414.7 parts per million.

While levels of so-called greenhouse gases such as CO2 have been increasing alarmingly, Colton says that the station has also detected a worldwide decrease in the presence of chlorofluorocarbons (CFC), a stratospheric ozone depleter. Sometimes referred to as the “good” ozone, the stratospheric ozone layer reduces the effects of detrimental radiation by filtering the sun’s harmful UV rays, protecting the planet and its inhabitants.

Darryl Kuniyuki and David Nardini release a ozonesonde.

“In the 1970s, the countries of the world agreed to abide by the Montreal Protocol and banned the use of these molecules, which were used in refrigeration, vehicle air conditioners and certain kinds of industrial foam,” says Colton. “They were removed from production voluntarily and ever since, we have seen a worldwide decrease in them, with one small exception. A few years ago, we detected a sudden increase in CFC-11, which was later determined to be coming from illegal production in China.”

As new chemicals come out, Colton says that the station also monitors replacements for CFCs because some are known ozone depleters and many are also greenhouse gases that contribute to global warming.

Located on eight acres of U.S. Department of Commerce property, Mauna Loa Observatory is serviced by a road owned by the state that meanders up through Mauna Loa Forest Reserve.

The observatory is manned by seven fulland part-time station technicians.

Although the station is built on relatively “recent” lava flows, natural lava barriers protect it, and it is monitored continuously by several USGS seismometers in case of an eruption or other seismic event.

“We’re associated with at least 30 different scientific organizations and we form the base for a lot of critical scientific knowledge,” says Kuniyuki, who has been a station employee since 1982. “Research is good. We’re proud of the work we do as a world-class facility that benefits the public, and indeed, the entire planet.”

For more information, visit esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/obop/mlo.