He’s Got The Beat

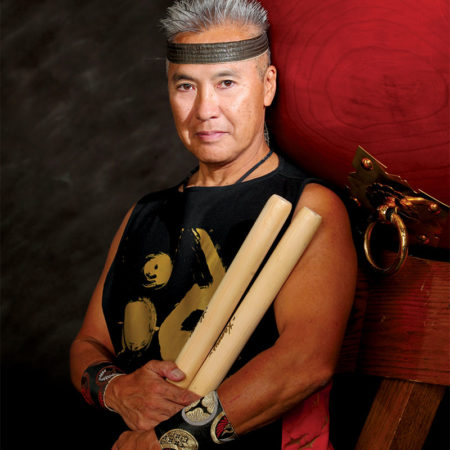

The good vibrations keep coming from taiko virtuoso Kenny Endo, who lives life marching to the beat of his own drum.

Who else can say they’ve performed for Michael Jackson and Princess Diana, have a day proclaimed to them in Honolulu and, most recently, be named to the United States Artists’ 2022 class of Fellows? None other than triple threat Kenny Endo, one of the world’s most prolific taiko performers, composers and teachers.

Those grand feats only brush the surface of all that Endo has accomplished. And while the latter is only the most recent, it was an honor, nonetheless. It was just last week when Endo was recognized next to 63 fellow artists across 10 creative disciplines, including architecture and design, dance, film, traditional arts, visual art and writing. The organization at the helm of the project, United States Artists, puts an emphasis on supporting a broad register of creative people — an effort even more pertinent now given that some artistic avenues, like Endo’s performing arts, have taken a backseat due to the pandemic.

If he’s not performing taiko, then Kenny Endo is teaching it, like in this photo that dates back to Taiko Center of the Pacific’s debut in 1994.

Long before his impressive list of accolades, though, Endo was just a boy in Los Angeles who was entranced by the beat of a drum.

“When there were parades, I would always run down just to hear the cadence of the drums because I like that vibration,” he remembers.

As he entered his teenage years, Endo would jam out to rock’n’roll — namely The Who, Jimi Hendrix and Cream — and became rapt by other musical genres including jazz, funk and Latin. He was passionate about playing the drums and was even a member of his high school band and orchestra, but it wasn’t until he witnessed a performance by the San Francisco Taiko Dojo, which is the first kumi daiko (ensemble drumming) group to form outside of Japan, in 1973 that he had that “aha” moment, thinking, “This is what I want to do with my life.”

Whether he’s performing in front of one or two people, or 10,000, taiko master Kenny Endo has the same philosophy: just do your best. PHOTO COURTESY KENNY ENDO

“When I saw taiko for the first time, it was the sound that you could feel down to your bones that pulled me in,” he recalls. “It was also part of my heritage that I wanted to know more about.”

There came a time in Endo’s early adulthood when he stood at a crossroad: Move to New York City to become a jazz drummer or take a leap of faith across the Pacific Ocean to study taiko in Japan.

“I felt that doing taiko would be a little more unique, and also I had an interest in going to Japan because I had never been there, although I’m ethnically Japanese and my father was born there and my mother is a second-generation Japanese American,” he shares. “I had an interest in meeting my relatives and learning more about my culture and taiko. After thinking about it, it was obvious that was the direction I wanted to go in.”

Whether he’s performing in front of one or two people, or 10,000, taiko master Kenny Endo has the same philosophy: just do your best. PHOTO COURTESY KENNY ENDO

What intended to be a one-year stay, wound up as an entire decade of complete immersion in the art of taiko. While there, he was involved with Miyamoto Unosuke Shoten, a taiko company with roots that date back to 1861. He was also named the first non-Japanese national to receive a natori (stage name and master’s license) in hogaku hayashi (classical drumming) — a recognition that ranks high on the list of life’s most cherished moments.

“That was a great honor. As far as classical music goes, I still feel like a student. There’s so much to learn,” shares Endo, who celebrated his 45th anniversary as a taiko performer in 2020. “There’s a saying in Japan — kiri ga nai — which means there’s no end to it. It’s almost like the more you study, the more you realize you don’t know. As long as I can try to keep learning, expanding and improving, it will feel fresh, and I’ll have this excitement about learning and practicing as well as performing, too.”

Endo’s authenticity and gracious state of mind could possibly be the reason for his success. Though, his devotion and admiration for the craft itself might have that beat.

Throughout his decadeslong career, Kenny Endo has dabbled in all types of genres related to taiko, including classical and modern. PHOTO COURTESY KENNY ENDO

Taiko, which quite simply means drum in Japanese, has been around for 2,000-plus years in The Land of the Rising Sun. The instruments range from hand-held to larger-than-life size and are often used as accompaniments in bands, theater and festivals.

Historically, the thunderous-sounding vessels were used to warn village people of fires or floods. And while here in Hawai‘i today, we have statewide sirens for that, the love for taiko persists, thousands of years — and miles — later.

To carry forward the practice and share all that he’s learned over his near five-decades long career, Endo, with wife Chizuko, established the Honolulu-based Taiko Center of the Pacific in 1994. He, alongside several other instructors — some of whom began at the school as just students themselves — teaches taiko to anyone who wishes to learn, from keiki to kūpuna and everyone in between.

PHOTO COURTESY KENNY ENDO

“The 10 years I spent in Japan were very valuable to me professionally, being able to study with some great masters and perform with some incredible musicians,” says Endo. “I feel that a lot of people in the United States or outside of Japan do not get that opportunity, so I feel almost like a bearer of the tradition to share that with people who are interested.”

Though the pandemic has put a serious strain on classes (which are currently taking place over Zoom) and performances, Endo looks forward to the few occasions he gets to be on stage, including a recent performance on Feb. 4 at University of Hawai‘i and a collaborative music/dance event at Windward Community College Feb. 26-27 (visit outreach.hawaii.edu/artists for more information).

“All of the performances are really important to me,” notes Endo. “In fact, I always tell my performers that no matter if there are one or two people in the audience or there’s 10,000, you have to approach it in the same way.

“There’s always going to be somebody who’s seeing taiko for the first time, or possibly seeing taiko for the last time, so there’s a responsibility to do your best and prepare for the performance.”

At the heart of it all, Endo always circles back to the visceral feeling that a taiko performance offers its listeners.

“I just hope that (the audience) experiences it not only as entertainment and something they can enjoy … but also I think the sound of the drums, especially taiko, is so deep in you that it kind of takes us back to something more primal,” he says. “In fact, they think that taiko is similar to the heartbeat of a mother when you’re in the womb. In that sense, in not just taiko, but music (in general), it has the potential to heal people, transform people and inspire people. I know that when I’ve gone to see some really great music or performers, I’ve been inspired that way, so I hope that in some way that our music can do that (for others).”

Come spring, Endo will finally embark on his 45-year anniversary tour — two years delayed by the pandemic — with his contemporary ensemble, comprising musicians from a variety of backgrounds. Together, the unit will visit 12 states to play a fusion, “East meets West” concept, according to Endo.

“For a lot of people who play taiko, there’s no melody,” he explains. “Sometimes the bamboo flute will play traditionally, but I like to combine it with other instruments, such as Japanese instruments — which are koto, shakuhachi and shamisen — but also with Western instruments … (On the tour), I combine things like a vibraphone and ‘ukulele with the traditional bamboo flute and shamisen and koto as well.

“If we’re talking about music that brings people together, I think if people from different cultures and backgrounds can get together and work and create something, that’s like a microcosm of the real world,” he adds. “It’s the potential for people to create rather than destroy; to be productive rather than destructive.”

To say that Endo’s calling-turned-career has been triumphant would be an understatement.

As he looks toward eventual retirement, Endo names aspirations he hopes to complete first, which include securing a permanent home for Taiko Center of the Pacific, creating a taiko philosophy/spiritual practice and finding successors to keep the tradition alive.

In the meantime, he’ll continue doing what he loves most: create and teach, with his taiko in tow.

“When you look at the world right now, there’s so much turmoil going on in all these different fields, and I think taiko — and art in general — is a way people can come together to inspire and heal and give them hope.”